Insights Article

How can a breakaway political party succeed in the UK?

Brexit has turned the British political establishment on its head, and both major parties are deeply divided over the issue of the day: as of this morning, seven Labour MPs have split off from the main party to sit in parliament as The Independent Group. Whether they’re going to be followed by a Conservative march out – as Jacob Rees-Mogg’s prophetic calls that should Theresa May fail to deliver Brexit, the Conservatives would experience a split as momentous as 1846 portend, remains to be seen.

It’s not only in the UK that upstarts are having their time in the sun – see, for example, the furore around Howard Schultz’ US presidential run – but smart insurgents have realised that, in democracies like the UK’s, it’s constituencies and not voters that matter. Go for constituencies, and you can recreate the success of the Scottish National Party (or indeed Italy’s Northern League) – but go for broad appeal, and you wind up with very popular electoral blowouts: think a British Ross Perot. What – then – are the constituencies to play for as either party, or for new ones?

Clusters spends a great deal of its time analysing consumers’ needs, barriers and motivations, usually after an extensive psychographic survey, putting those consumers into self-similar groups we call segments, and then using those segments to provide a paradigm to guide corporate growth. However, given the time pressure facing Smith, Berger, Umunna et al. and Rees-Mogg as the Brexit clock ticks down, we thought that, just in this case, we would expedite the process by instead grouping constituencies together using publicly available data from the 2016 referendum result, 2017 general election, and demographic and political data from the Annual Population Survey, the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings and the House of Commons Library. Here’s what we discovered.

The Rural Heart of the Conservative Party

It’s often been remarked that both of the largest British political parties are broad churches. This could not be truer than for the segment that encompasses 212 of the Conservative’s 317 seats: Rural Tories, making up 221 seats overall. With an average Conservative vote share of 57%, a quarter of their over-16 population also over 64 and a strong sense of English identity, these leave-voting, rural seats (40% of them are classified as “village[s] or smaller” settlements, against a fifth nationally) are the bulwark of the Tory Party. These contain most of the scions of the Conservative left, middle and right – Theresa May’s, Dominic Grieve’s and Jacob Rees-Mogg’s (not to mention the Speaker’s, John Bercow) seats all come from this segment, and the government knows it – nearly 70% of the Cabinet does too. This isn’t a segment anyone’s very likely to split – Tory insurgents will need to reconcile themselves to either taking over this institutional part of the party apparatus or settle for smaller targets.

The Big Split in Labour

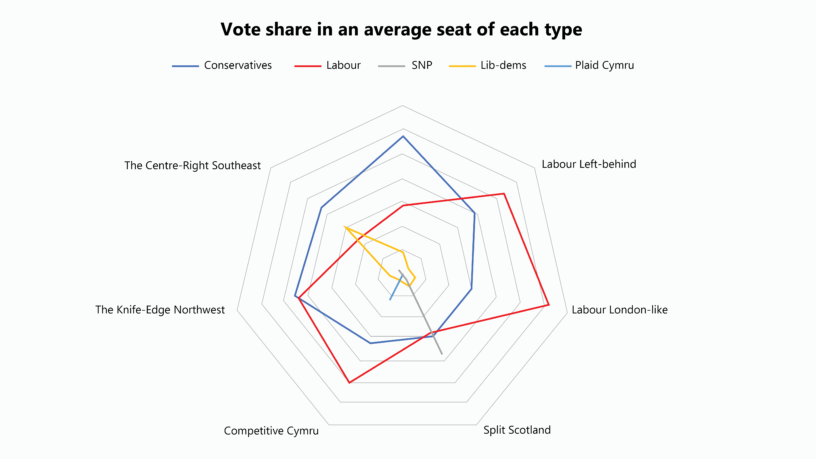

Outside of Scotland, Labour has the two segments with the biggest splits on Brexit. The problem for party planners is that the they split either way. The Labour Left-Behind gave 99 of its 134 seats to Labour in 2017 with 132 voting to leave the European Union, where Labour London-like gave the party 103 of the 121 at play, with just 28 seats voting for Brexit – together, they contribute 202 of Labour’s 256 seats. The Shadow Cabinet is similarly split: eleven members of the shadow cabinet are from Labour Left-Behind constituencies, and twelve are from Labour London-like.

Labour Left-Behind constituencies conform to some well-worn stereotypes: they’re poorer and growing more slowly, with more people working in manufacturing than the rest of the country. They identify with being English, experience higher unemployment and are more likely to vote for UKIP. They’re spread fairly evenly over the large towns to the middling cities in the Midlands, the North and Yorkshire, with only a few tendrils penetrating into the South or East, and none at all into London or Scotland. But the stereotypes only go so far – MPs from the centrist wings of both parties in opposition to party policy have made their camp here: this is where Yvette Cooper, Frank Field, Nicky Morgan and Anna Soubry all call home.

Although half of Labour London-like constituencies are in London, the spirit of this segment persists wherever there are celebrated foreign flags in windows, The Guardian on shelves and avocado on toast. These constituencies are young, well-off, highly educated and ethnically diverse. 85% are in cities and none are found in anything less than a medium-sized town. Although the cabinet as a whole is fairly evenly split between these two segments, many of Jeremy Corbyn’s closest circle – John McDonnell, Diane Abbot, Emily Thornberry and of course Jezza himself – are from this segment: maybe it’s no surprise that Tom Watson, whose elevation to deputy leader of the opposition was in part a sop to hold the party together, is the most senior member of the cabinet from Labour Left-Behind.

We originally thought that a split in the Labour party would break apart the marriage of convenience between these two halves, but this morning’s events actually speak to a much more common business issue: overcrowding in the most fashionable targets. Jeremy Corbyn’s brand of socialism has been wildly popular in Labour London-like, but now the Independent Group is exploiting his party’s less popular stance on Europe and antisemitism to try to make a play for the same segment: six of the seven founding members of the Independent Group sit for Labour London-like seats.

The State of the Nation(s)

What about the non-English nations that make up the United Kingdom? We had to leave Northern Ireland out of our analysis, accounting for 18 parliamentary seats, as the bodies which collected the information we used for most of our segmentation did not cover Northern Ireland, but it’s likely that this would have split off early from the main groups due to its distinctive political makeup. Politics is split with ten seats to the DUP and seven to the abstentionist Sinn Féin; this is also one of the few regions of the UK where remain-voting seats outnumber leave-seats two to one.

Split Scotland – encompassing all but two of the Scottish seats – is less homogenous than the SNP’s political dominance would at first imply. There are some peculiarly Scottish quirks – higher public sector employment and an overwhelming support for the EU (only two seats mustered Leave victories) among them – but despite the SNP’s explosion into the 2015 election, the other parties now hold 22 of the 57 seats up for grabs, reflecting an average seat with a 37:28:28:6 vote share for the SNP:Conservatives:Labour:Liberal Democrats. Income, age distribution, education, and unemployment are all roughly in line with other seats, when considered as a whole across the Union. The population tends to live in small communities or a small number of “core” cities (Edinburgh and Glasgow) – 19% against the 35% living in villages or smaller settlements, with another 35% in small or medium sized towns – unsurprising given Scotland’s mountainous terrain. There’s clearly a route to Whitehall for one of the British parties here, particularly given the recent criminal charges against former SNP leader Alex Salmond, but it’s not likely to come from splitting the anti-SNP vote still further.

Competitive Cymru is a little different from the other two national regions. For a start, six Welsh parliamentary seats are characterised as Rural Tories (Brecon and Radnorshire and Montgomeryshire) or Labour London-like (Cardiff Central, North and South and Penarth, and Swansea West). Of the 34 seats left, 24 are held by Labour and 6 by the Conservatives, giving Plaid Cymru third-place representation in Competitive Cymru. These seats share some similarities with Labour Left-Behind – they’re poorer, older, comparatively manufacturing-oriented – but unlike those seats they’re relatively ambivalent on the EU, have high levels of public sector employment and, most notably, skew towards living in smaller towns and villages rather than larger towns and cities. In the event of a split, an already-split ballot might make it easier to nose over the line in some of these seats, so long as the new party could speak to these concerns and not get tarred by accusations of Westminster machinations.

The English Battlegrounds

That leaves us with two English segments covering 34 and 31 seats each. The Knife-Edge Northwest is keenly poised between Labour and the Conservatives, taking 15 and 19 seats respectively and 45% and 46% vote share each in an average seat. Nearly half of these seats are in the North West, and a further 18% are in the West Midlands. These are middling-sized towns with nearly 40% of young people (18-24) in full time education and rapidly growing economies. On Brexit, they form a microcosm of the UK as a whole: the average constituency had 52% in favour of leaving the European Union. Seven members of the cabinet and shadow cabinet come from these constituencies, including the likes of Jeremy Hunt, Amber Rudd, Peter Dowd and Cat Smith. Naturally, further consternation in either party would likely tip this fine balance in favour of the more stable party, but it’s tempting to believe some kind of centrist unity pitch might have some value here.

The Centre-Right Southeast is where the Liberal Democrats retreated after their defeat in 2015, with eight of their twelve seats as of 2017 coming from this 31-seat constituency: nineteen of the remaining seats have Conservative MPs. A third of these seats are in the South East, a quarter in London, 13% in the East of England and two in Scotland, and those outside of London are typically large towns, rather than other cities. These seats are Europhilic, extremely well-to-do (the median income is £5,500 higher than the nationwide average) and well-educated, with almost 90% of the population working in services. They’ve also produced MPs with a wide range of ideologies: Conservatives include arch-Eurosceptics such as Dominic Raab and Graham Brady bundled together with comparative moderates like Tom Brake and Zac Goldsmith. This is most likely the place to make the Conservative Europhile argument for splinter groups from that party, but probably isn’t a place to look for Labour seat gains.

From a Description to a Strategy

So far, this is just a description with the odd recommendation about fissures potential rebels might wish to exploit – but what sets Clusters’ work apart is our track-record of converting clever ideas into actionable policy, and after a split, the “business problem” any group must face is this: how do I stabilise my rocky political segment into a broader political movement outside of my little segment? And how, if I represent one of the established parties, would I recover from such a rift? To do this, we can look at the proximity of these segments in the multidimensional space of the segmentation. What the parties should do depends a lot on where the trouble starts.

Start with the rebels: we think it’s fairly unlikely a new pan-British political movement is going to find much luck if it starts in Northern Ireland or Split Scotland, so we can discredit those two sets of seats. The target for an insurgency coming from either of The Knife-Edge Northwest or The Centre-Right Southeast would likely be best served by trying to march into Conservative territory in Rural Tories, though probably from quite different perspectives. To indulge Mr. Rees-Mogg a little, a centre-right move on the Tories would probably be somewhat Whiggish, coming from wealthy, liberal Europhiles, while a Northwesterly approach would be a little more Tory – playing up the political advantages of scepticism about Europe, belief in a muscular state and the wealth of high-profile Conservatives in this area. Of these, The Knife-Edge Northwest probably has the advantage in transplanting its local appeal. A Labour insurgency speaking to Welsh concerns would have a big prize at play: the next logical step for one starting in Competitive Cymru would be to make a play for Labour Left-Behind, the second-largest segment, binding together Labour sentiments and Euroscepticism.

How could the big segments recover after a breakaway faction, or build out their gains to avoid a hung parliament in the next election? Rural Tories, Labour Left-Behind and the Knife-Edge Northwest are all sensible targets for each other: though quite possibly a shift in the balance of power caused by a split would decisively turn the competitive seats in each of these areas to one party or the other.

That leaves Labour London-like politically isolated – almost as far from the other segments as Scotland’s or Wales’ groups: these 121 seats are going to form the battleground between the Corbyn Labour party and the Independent Group. If, breaking with historical precedent, this new grouping captures this territory, expect a smart Labour rump to swing towards trying to unite Labour Left-Behind and the Knife-Edge Northwest and an ambitious Independent Group building out centrist, Europhile appeal into the Centre-Right Southeast.

To learn more about how Clusters uses segmentation and market research to help your business grow, call us on 020 3950 6624 or get in touch here.

Want these kinds of results?

We’d love to talk with you about how our insights could help your business grow. Drop us an email at hello@clusters.uk.com or call us on +44 (0)20 7842 6830.